Introduction

Customer acquisition alongside accurate risk pricing are the two cornerstones of a successful flood insurance program. Flood risk modeling has improved such that private insurers are increasingly offering coverage for the once “uninsurable” peril. However, a relative lack of consumer demand compared to other property insurance offerings still gives carriers hesitation when trying to evaluate whether they should invest in launching their own private flood programs. Utilizing available data, Milliman has developed a take-up rate model that can help private insurers better understand how to test their products, acquire new business, and grow their written premium. In the coming months, we will outline key elements in assessing the opportunities within the emerging private flood market.

Flood insurance is changing rapidly between the growth of the private flood market, the launch by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) of Risk Rating 2.0, and the continued impacts of climate change, aging infrastructure, and residential development. The current residential flood market has roughly $4 billion in written premium as of today, but Milliman estimates the total flood market to be between $37 billion and $47 billion. Despite nearly every county in the United States having experienced a flood event in the past 25 years according to FEMA, only 4% of homeowners are insured for flood today. Recent hurricanes and the associated flooding continue to put flood insurance in the spotlight and demonstrate the need to close the protection gap. The starting point for any insurers looking to launch a private flood insurance product is: If I build it, will they come?

Take-up rate drivers

Utilizing publicly available data from OpenFEMA, we analyzed the percentage of homes with flood insurance (take-up rate) across the continental United States at the census tract level. We excluded areas inside the Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs), where purchasing flood insurance is often not a consumer choice but mandated as a condition for obtaining a federally backed mortgage. As one might expect, we found that consumer behavior varies substantially at a local level, and drivers of flood insurance take-up rates are inherently different in coastal and noncoastal areas.

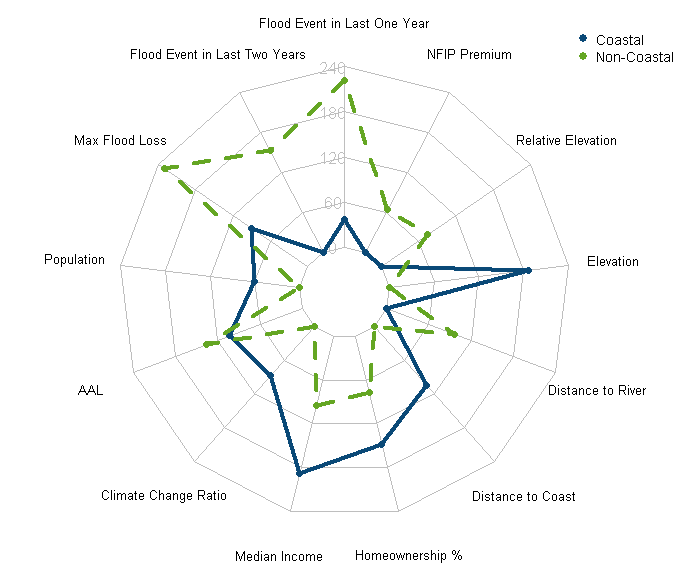

Figure 1 highlights the primary variables that drive voluntary flood insurance purchasing patterns in both coastal (blue solid line) and noncoastal (green dashed line) census tracts. The further out on the axis each line extends, the more important the variable are to predicting flood insurance take-up rates.

Figure 1: Variable importance for predicting flood take-up rates

The most important variables for predicting take-up rates in coastal areas are defined by the general risk of the area as measured by variables such as elevation, distance to coast, and average annual loss (AAL), as well as the financial means to buy flood insurance as measured by variables such as median income and homeownership. AAL is defined as the expected flood losses in a year; in our analysis AAL is estimated using the KatRisk SpatialKat Flood and Storm Surge Models. In addition to including the AAL, we also used KatRisk model output to estimate the relative increase in AAL in 2050 under a “medium” sea-level scenario.1 The inclusion of this “Climate Change Ratio” variable means that areas more vulnerable to sea level rise by 2050 are already seeing higher flood insurance take-up rates, all else being equal.

In noncoastal areas, larger and more recent prior events have a powerful positive impact on take-up rates, as seen by the high importance level for flood events in the last one and two years and by the maximum recent flood event as measured by National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) losses. AAL is also a key driver of take-up rates, as consumers with more flood risk purchase insurance more frequently. Additionally, geographic predictors of inland flooding, like distance to the nearest river and elevation relative to the surrounding area (relative elevation), are also highly predictive of flood insurance take-up rates. Though median income and homeownership percentage are less important in the noncoastal areas relative to the coastal, NFIP premium itself is also predictive of take-up rates. Higher NFIP premiums intuitively translate to lower take-up rates, which further highlights the price sensitivity of consumers.

The OpenFEMA data provides valuable insight into who buys flood insurance from the NFIP today, but more importantly it can be used by private flood insurers to understand how to acquire customers who are not currently insured by the NFIP. With the private flood market only 10% of what it could be in terms of written premium, this is one of the largest sources of untapped revenue available to property insurers today. It is also an opportunity to prove that the insurance industry can play a key part in making communities more resilient to natural disasters and climate change. In the following sections, we highlight four takeaways from our OpenFEMA take-up rate modeling that current and prospective private flood insurers should consider.

Location, location, location

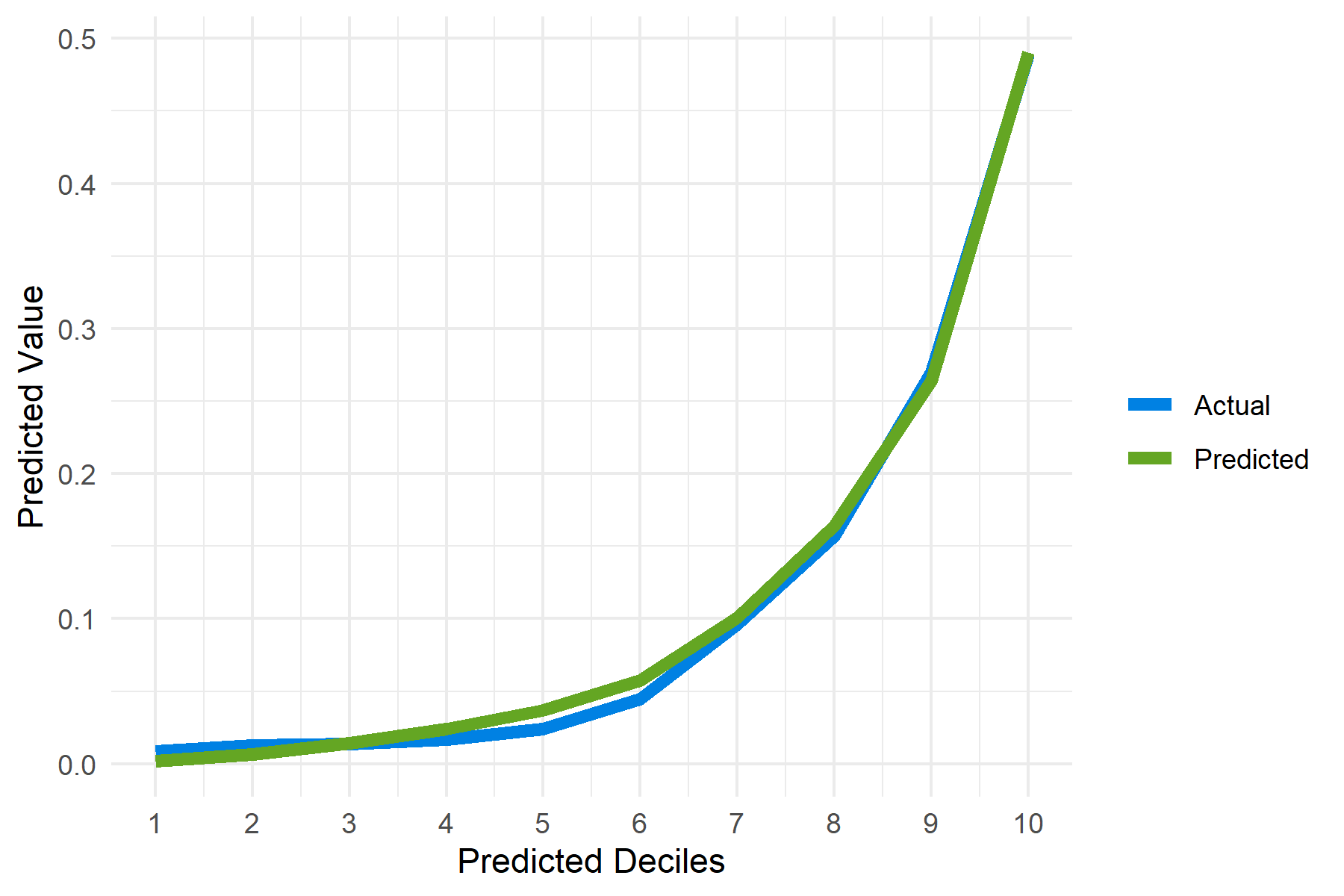

A commonly expressed concern of private insurers is that flood insurance consumer demand is limited across the country. However, many within the insurance industry do not realize that flood insurance is voluntarily purchased at a high rate in many areas of the country today. As shown in Figure 2, the top 10% of coastal census tracts have a combined take-up rate of almost 50% (outside of the SFHAs). The two lines shown in Figure 2 are averaged values of the observed take-up rate (blue line) seen in the data, alongside our predicted value (green line) from the model. The overlapping of the two lines demonstrates our model’s ability to systematically understand the underlying phenomenon in the data and report an accurate take-up rate based on the underlying variables. This means that not only do flood insurance take-up rates vary at a high level across localities, but that there is a systematic pattern to this variation that can be explained by flood-relevant risk, demographic, and geographic data. A similar plot for our noncoastal model would have a smaller range of take-up rates, 0.2% to 10%. While this is still a good amount of variation, it also reflects the overall lower take-up rate outside of coastal areas.

Figure 2: Coastal non-SFHA take-up rate lift chart

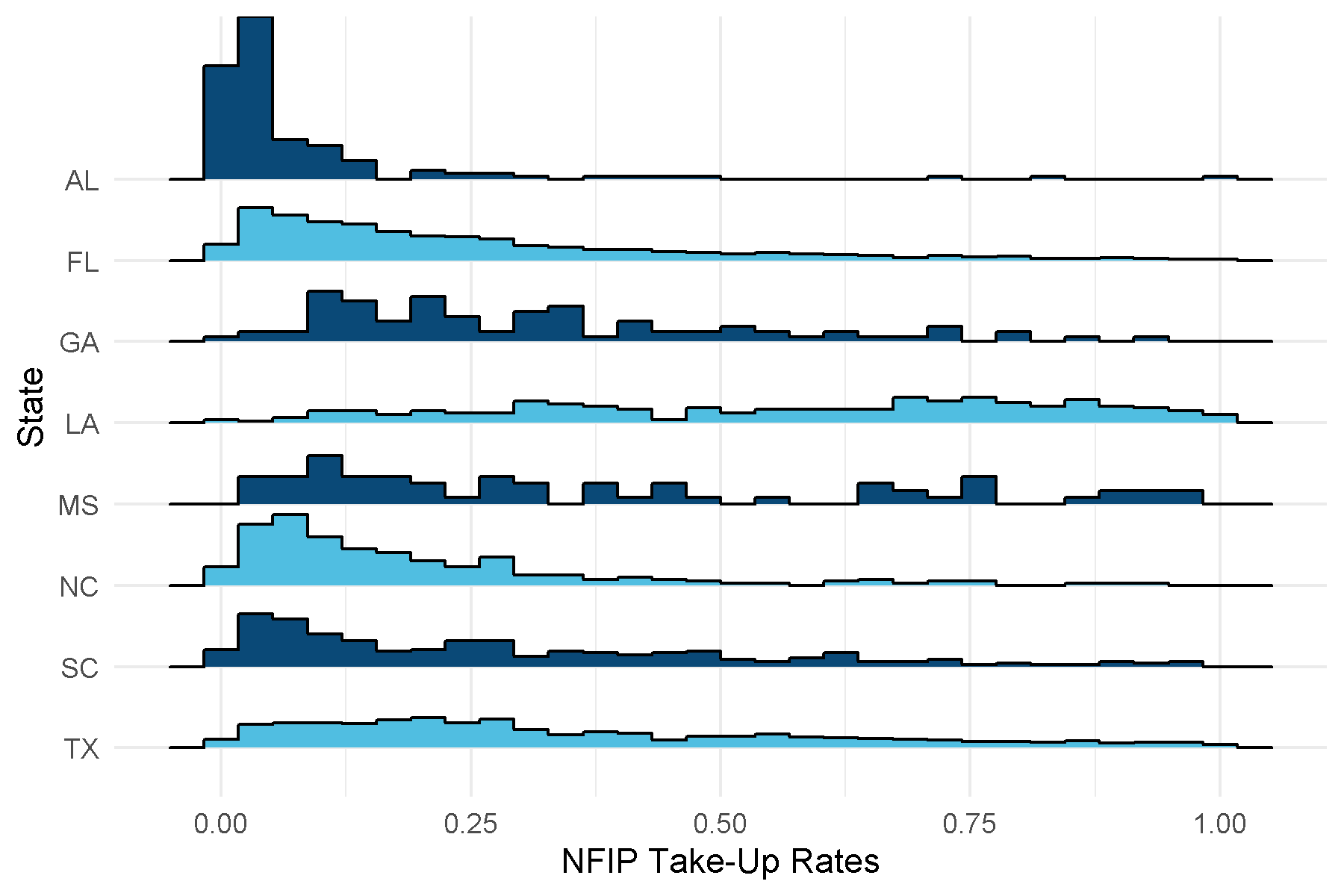

This wide disparity in take-up rates is even more pronounced at the state level. Figure 3 shows the distribution of coastal take-up rates for important flood states in the southeastern United States. Each line is the histogram of census tracts with that take-up rate level. The distribution in Louisiana demonstrates how widely the take-up rates can vary within a single state. The long tails for all of these states show that large market penetration is possible, but not currently widespread. Our take-up rate model can help identify the areas with the best potential for market penetration.

Figure 3: Distribution of take-up rate for coastal non-SFHA areas

Consumers (attempt to) purchase based on their risk

Our analysis validates that consumers attempt to purchase flood insurance when they think they are at risk. Consumers purchase flood insurance more often in coastal areas when they are closer to a coast and elevated near sea level, and more often in noncoastal areas when they are closer to a river and at lower elevations relative to the surrounding area. They also purchase more where climate change increases the risk of coastal flooding, and if they are in an otherwise risky area as measured by AAL for inland flood.

While our analysis was done at the census tract level, it stands to reason that, all else being equal, these purchasing patterns would translate to the property level. Insurers that are able to market to consumers with these risk characteristics should find higher probabilities of success. Though some of these insureds may have an NFIP insurance policy already, the majority often do not—allowing insurers to grow the flood insurance market and help close the protection gap. Consumers have limited knowledge of their flood risks today, particularly outside the SFHAs where detailed FEMA flood maps are not available. Yet they still show a purchasing pattern that relates to several complex risk characteristics. Companies have another opportunity to grow the flood insurance market by providing risk education to consumers and agents.

For insurers that do not currently have private flood programs, understanding where flood products will be more in demand is a valuable tool for financial planning and pro forma development, product development, and state prioritization. Low consumer demand may be a concern for property insurers at this time, but it is not an insurmountable obstacle. Flood product feasibility can be rigorously tested as opposed to dismissed without thorough consideration. The latter comes at the risk of allowing competitors to provide more comprehensive coverage to your customers and gain a foothold in an emerging market.

Consumers are price-sensitive

Flood insurance is often considered an extra expense if it is not mandated to be purchased. In both of our models, we found median income for the area to be positively correlated with more take-up rate. We also found NFIP premium to be negatively correlated in the noncoastal areas. This gives credence to the intuitive reasoning that financial means drives the purchase of flood insurance while high premiums discourage purchasing.

By replacing NFIP premium with an alternative premium option within a take-up rate model, insurers can estimate their own take-up rates for an actual or hypothetical product, analyze the market potential, and develop a better understanding of products for marketing purposes.

With the wide differences in flood risk estimates at the property level, take-up rate modeling can provide valuable insight into how a private flood product will perform. By replacing NFIP premium with an alternative premium option within a take-up rate model, insurers can estimate their own take-up rates for an actual or hypothetical product, analyze the market potential, and develop a better understanding of products for marketing purposes. Insurers could also look to develop alternative options such as low limit products for voluntary purchase that allow insureds to obtain affordable, if limited, coverage.

Price sensitivity may become even more important with FEMA introducing Risk Rating 2.0. Insureds receiving rate increases may look to shop or even not renew their flood coverage. The private market has an opportunity to provide alternative price points and coverages to prevent consumers from going uninsured, and even gain previously uninsured customers as Risk Rating 2.0 increases awareness of flood risk. Understanding where these customers are can be a huge advantage for insurers to grow their private flood business.

Insurers have an opportunity to prepare communities for the next flood

Previous research2 has shown that flood insurance take-up rates increased in the year immediately after a flood event. This change in people’s purchasing behavior slowly disappeared over a nine-year period and was found to be independent of both the event size and cost. Consistent with this study, we found increased take-up rates in the first year after an event, and smaller increases in years 2 through 8 after an event. However, we also found the size of the loss as measured by NFIP paid losses to be significant. Both studies consistently show that flood insurance demand increases substantially after a flood event.

All else being equal, for coastal homes the probability of purchasing a flood insurance policy after a flood event increases by a factor of 1.13 compared to before a flood event. Our noncoastal model also found a post-flood event increase in the probability of purchasing insurance by a factor of 4.57 with all else held equal. This shows that, even though flood insurance take-up rates are lower in noncoastal areas (2% vs. 12% in coastal areas, on average), substantial purchasing can occur following a flood.

Though ideally consumers would purchase flood insurance before an event occurs, these results indicate there is an opportunity for insurers to provide homeowners the future protection they seek immediately after a flood event. Insurers that can position themselves to provide flood coverage when the demands arise and can figure out how to keep these policies renewing in years without flood events will be rewarded as they help grow the market toward its potential.

Industry opportunities

The flood protection gap presents an opportunity for the insurance industry to build more resilient communities as well as a business opportunity. Many insurers are hesitant to get into a new peril such as flood, but for those willing the opportunity is there for the taking. Leveraging the OpenFEMA data to understand consumer demand is a valuable tool for maximizing this opportunity. In addition to the insights discussed above, we will continue our three-part series next with an analysis of consumer renewal behavior, followed by information on how to combine consumer demand modeling with your product to better understand and refine your flood insurance opportunity

Private flood insurers have long struggled to find a way to convince consumers of the need for flood insurance. A take-up rate analysis can help insurers identify the best areas to market and sell their products.

To learn more about Milliman’s flood research and how we can help click here.

1 Specifically, the KatRisk model output used projections based on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scenarios for regionally medium sea level rise by 2050, with 0.5 meters globally by 2100. This is generally considered to be a reasonable estimation of what will happen if, on average, global economies are able to stabilize and begin to reduce greenhouse emissions in the near future.

2Gallagher, J. (2014). Learning about an Infrequent Event: Evidence from Flood Insurance Take-up in the United States. American Economics Journal: Applied Economics, 206-233.